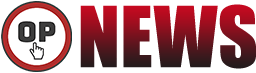

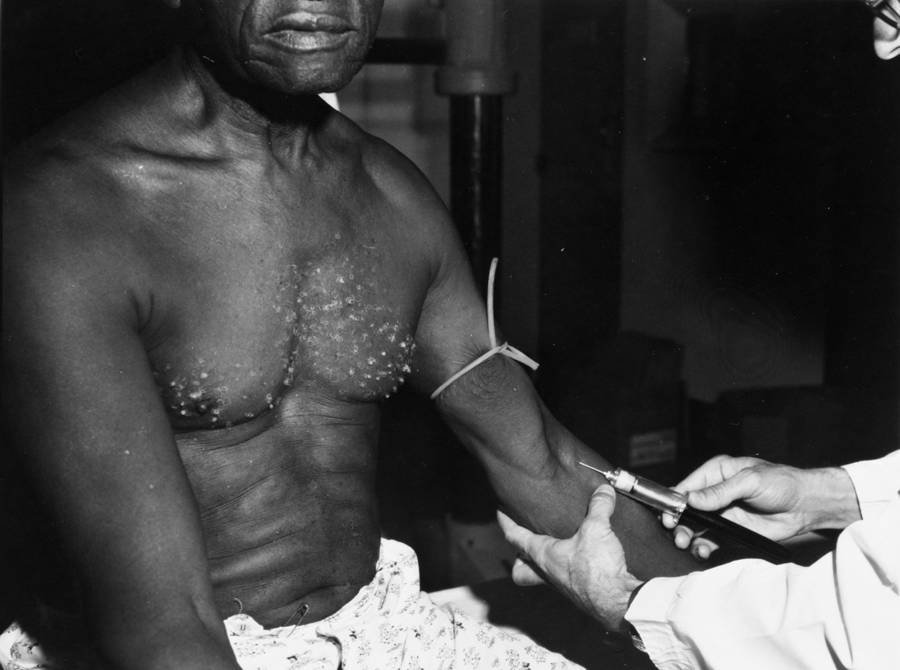

For 40 years, the U.S. government doctors behind the Tuskegee experiment tricked African-American men with syphilis into thinking they were getting free treatment — but gave them no treatment at all.

‘You Don’t Treat Dogs That Way’

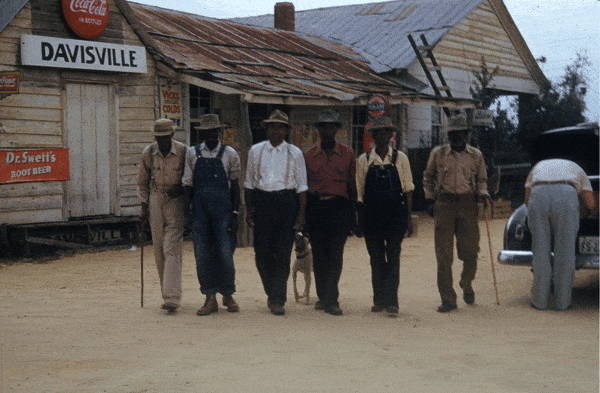

In the midst of the Great Depression in 1932, the U.S. government appeared to be giving away free healthcare to the African-American sharecroppers in Macon County, Alabama. There was a serious syphilis outbreak in this area of the country at the time and it appeared as though the government was helping to fight it.

However, it eventually came to light that the doctors let 622 men believe they were getting free healthcare and treatment — but actually gave them no treatment at all.

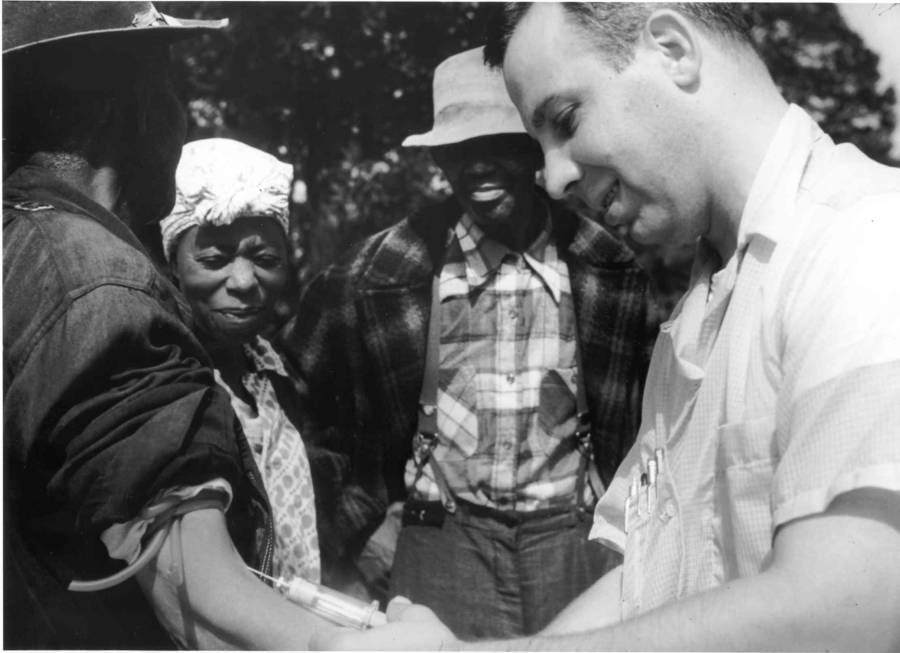

National Archives/Wikimedia Commons

Instead, the purpose of the Tuskegee experiment (a.k.a. the Tuskegee syphilis study) was to observe untreated black patients as syphilis ravaged their bodies.

“The Tuskegee Study Of Untreated Syphilis In The Negro Male”

The United States Public Health Service ran the Tuskegee experiment from 1932 to 1972. It was the brainchild of senior official Taliaferro Clark, but he hardly worked alone. Several high-ranking members of the Public Health Service were involved and the study’s progress was regularly reported to the government and given repeated stamps of approval.

Wikimedia Commons

Originally, the study’s directive was to observe the effects of untreated syphilis in African-American men for six to eight months — followed by a treatment phase. But as the plans were being finalized, the Tuskegee experiment lost most of its funding. The challenges of the Great Depression caused one of the funding companies to back out of the project.

This meant the researchers could no longer afford to give treatment to the patients. However, the Tuskegee doctors didn’t cancel the project — they adjusted it.

The study now had a new purpose: to see what happened to a man’s body if he didn’t get any treatment for syphilis at all.

The researchers thus observed the men who had syphilis until they died, lying to them about their condition to keep them from getting treatment anywhere else. They watched as their bodies slowly degraded and they died in agony.

“Black Belt”

US Public Health Service officials needed a location to conduct their study, and they found the perfect place in Macon County, Alabama. It was known as the “Black Belt” of the region, both because of the thick, dark soil that made land so fertile for agriculture and because of the large population of Black sharecroppers who made their living working the land, according to Tuskegee University. According to the US Census, 82 percent of Macon County’s population was Black in 1930, per “Bad Blood.” The region was very rural, and most sharecroppers were not well-educated. In Macon County, 227 out of every 1,000 African Americans could not read.

A predominantly rural, Black, and illiterate population was ideal for the purposes of the Tuskegee experiment. In January 1932, after seeing Macon Country, Dr. Parran declared, “If one wished to study the natural history of syphilis in the Negro race uninfluenced by treatment, this county would be an ideal location for such a study,” via The Philadelphia Inquirer. Dr. Clark echoed a similar sentiment, saying: “Macon County is a natural laboratory; a ready-made situation. The rather low intelligence of the Negro population, depressed economic conditions, and the common promiscuous sex relations not only contribute to the spread of syphilis but the prevailing indifference with regard to treatment.”

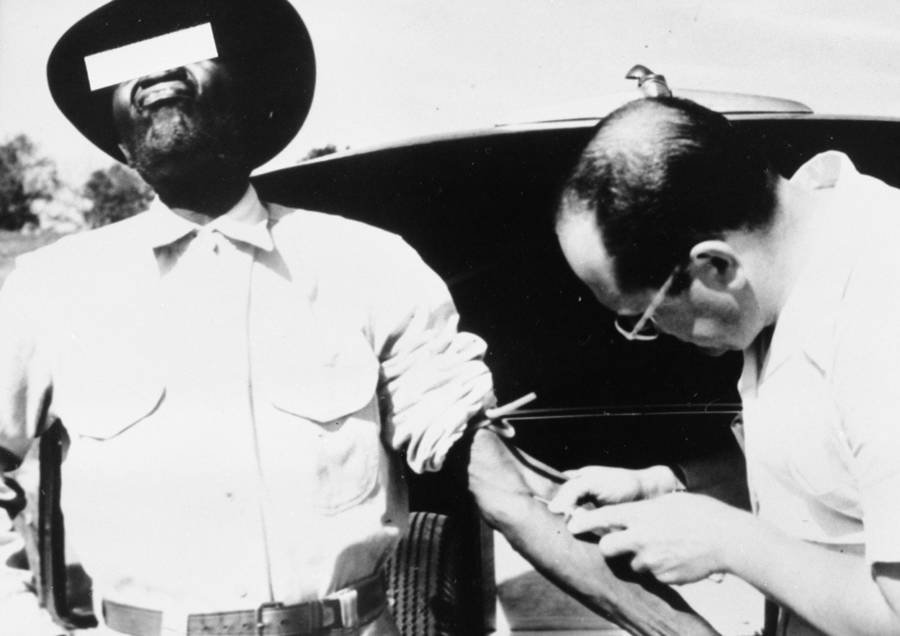

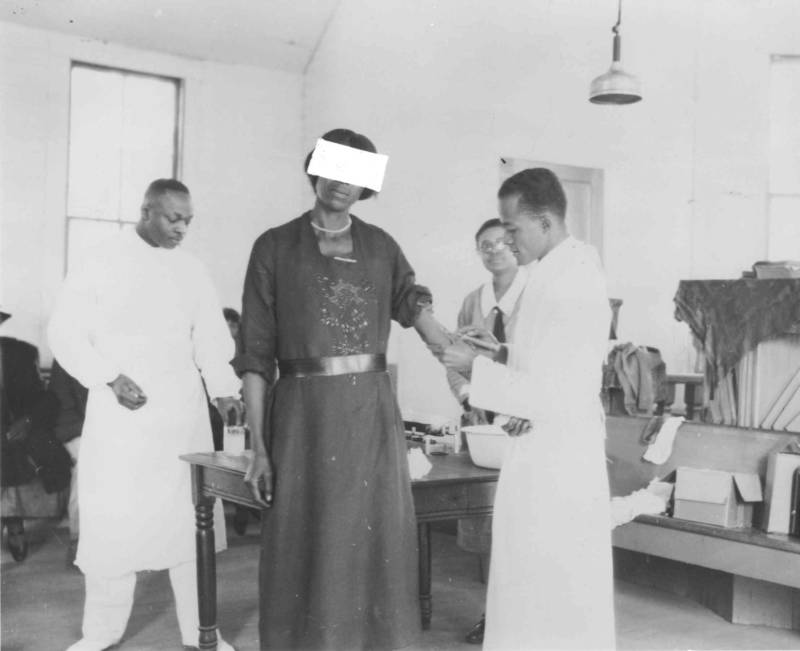

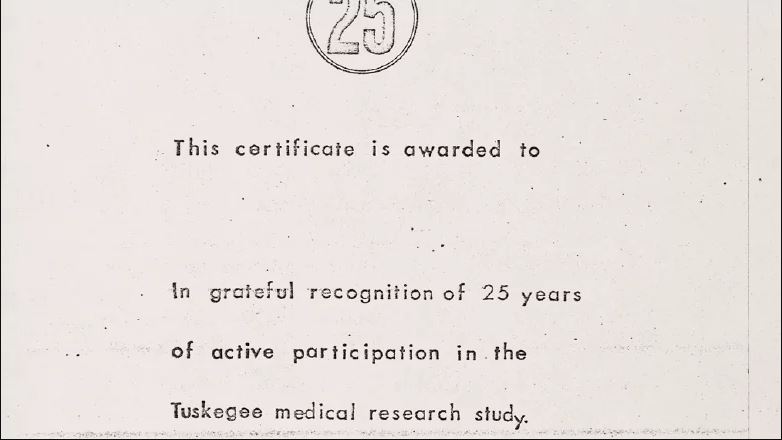

Tuskegee Subjects Were Compensated With Free Food and Medical Exams

Health officials initially recruited subjects to the study by offering them free medical care. Macon County was not a wealthy region, and health care was not always easy to come by for Black agricultural workers, so it was an enticing offer. However, some men were initially skeptical, suspecting that they were really being examined for military recruitment. To quell these fears, officials began including women and children in their examinations while still adding any eligible men they encountered to the study, according to McGill University.

In the 1930s, as the Great Depression worsened, the promise of free medical care was an exceptionally temping offer, particularly for an economically impoverished area. However, even the promise of free health care was not enough to entice some of the men to continue the treatments. So as the study went on, the subjects were offered more benefits, including extended medical treatment, free rides to appointments, hot meals on appointment days, medical exams, and even burial stipends, per Tuskegee University.

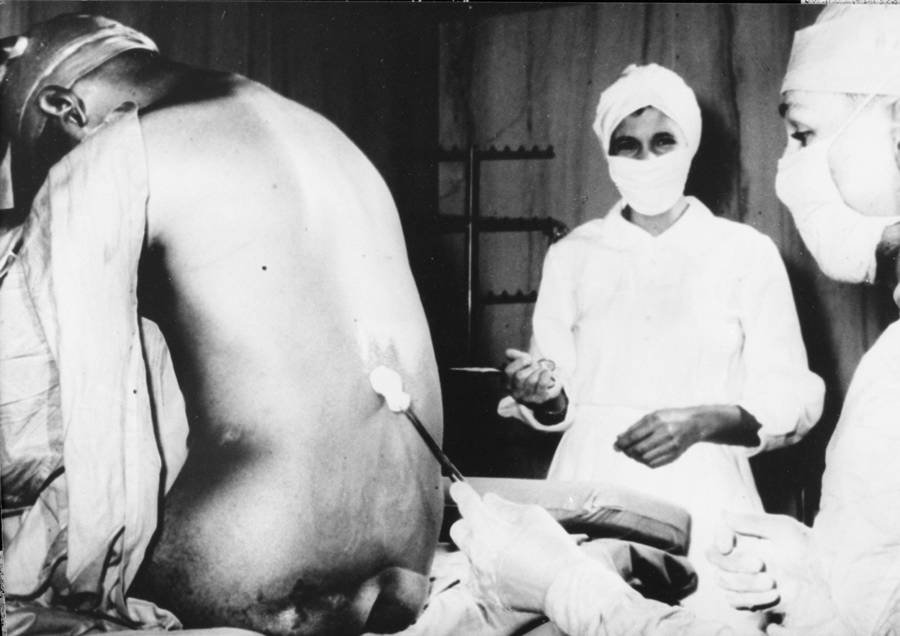

For some of the treatments, like the painful and ultimately unnecessary spinal taps, Public Health Service officials used a psychological tactic. Enticing them with the offer of a “special free treatment” for their “bad blood,” officials convinced many of the men to undergo the dangerous spinal procedure, according to The New Social Worker.

Deliberately Withholding Treatment

National Archives

When the Tuskegee experiment first began, doctors already knew how to treat syphilis using arsenic therapy. But he researchers deliberately withheld information about treatment. They told the patients that they were suffering from “bad blood” to keep them from learning about syphilis on their own.

The experiment was unquestionably illegal. By the 1940s, penicillin was a proven, effective treatment for syphilis. Laws requiring treatment for venereal diseases were introduced. The researchers, however, ignored all of this.

Dr. Thomas Parran Jr., one of the study’s leads, wrote in his annual report that the study was “more significant now that a succession of rapid methods and schedules of therapy for syphilis has been introduced.”

In short, he maintained that the Tuskegee experiment was more important than ever precisely because so many cases of syphilis were getting cured. This, he argued, was their last chance to study how syphilis killed an untreated man.

40 Years Of Death

National Archives

In all the years this reprehensible study was active, nobody stopped it. By the 1940s, physicians weren’t only neglecting to treat the men’s syphilis, they were actively keeping them from finding out there was a cure.

“We know now, where we could only surmise before, that we have contributed to their ailments and shortened their lives,” Oliver Wenger, a director for the Public Health Services, wrote in a report. That didn’t mean he was going to stop the study or give them the treatment. Instead, he declared, “I think the least we can say is that we have a high moral obligation to those that have died to make this the best study possible.”

In 1969, 37 years into the study, a committee of Public Health Service officials gathered to review its progress. Of the five men in the committee, only one felt they should treat the patients. The other four ignored him.

Ethics weren’t a problem, the committee ruled, as long as they “established good liaison with the local medical society.” As long as everyone liked them, “there would be no need to answer criticism.”

The Doctors Who Let The Tuskegee Experiment Happen

National Archives

It’s hard to imagine anyone wanting to be associated with such an experiment, let alone anyone from the historically black Tuskegee Institute and its staff of black doctors and nurses. But that’s part of the sad story behind the Tuskegee syphilis study.

The patients’ main contact point was an African-American nurse named Eunice Rivers. Her patients called the observation building “Mrs. River’s Lodge” and regarded her as a trusted friend. She was the only staff member to stay with the experiment for the full 40 years.

Rivers was fully aware that her patients weren’t being treated. But as a young, black nurse given a major role in a government-funded project, she felt she couldn’t turn it down.

“I was just interested. I mean I wanted to get into everything that I possibly could”, she recalled.

Rivers even justified the study after it went public in 1972, telling an interviewer, “Syphilis had done its damage with most of the people.” She also mentioned that the research provided value, saying “The study was proven that syphilis did not affect the Negro as it did the white man.”

Informed Consent

One of the main reasons the Tuskegee experiment was so unethical was because the study participants were never provided enough information to be able to give their informed consent. In fact, researchers deliberately withheld information about their disease and the true purpose of the experiment. An intern at the Tuskegee Institute’s hospital admitted, “The people who came in were not told what was being done. We told them we wanted to test them. They were not told, so far as I know, what they were being treated for or what they were not being treated for. [The subjects] thought they were being treated for rheumatism or bad stomachs. We didn’t tell them we were looking for syphilis. I don’t think they would have known what that was,” via “Bad Blood.”

The subjects were told only that they were being treated for “bad blood,” which could include any number of illnesses, from syphilis to anemia to simple fatigue. None of the subjects were told they were being treated for an STD, and as a result, many unknowingly passed it on to their wives or girlfriends. Because they were not aware what illness they were being treated for, subjects were also not given the option to leave when penicillin became readily available as a syphilis treatment, per the CDC. None of the patients were informed of the potential dangers, and none ever gave informed consent, making the Tuskegee syphilis experiment one of the most notorious and unethical studies in American history.

The Tuskegee Experiment Is Revealed To The World

National Archives

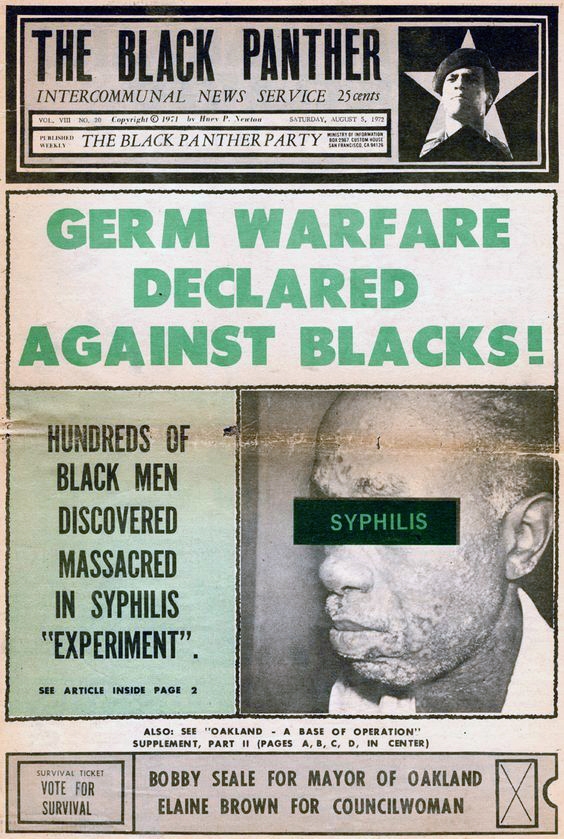

It took 40 years for someone to break the silence and shut the study down. Peter Buxtun, a Public Health Service social worker, tried staging several protests within the department to shut down the experiment. When his superiors continued to ignore him, he finally called the press.

On July 25, 1972, The Washington Star ran Buxtun’s story and the next day it was on the cover of The New York Times. The U.S. government had broken its own laws and experimented on its own citizens. Incriminating signatures from everyone in the Public Health Department were all over the documents.

Thus the Tuskegee experiment finally came to an end. Sadly, by then only 74 of the original test subjects survived. Approximately 40 of the patient’s wives had become infected, and 19 of the men had unknowingly fathered children born with congenital syphilis.

The Researchers Behind The Tuskegee Syphilis Study Refuse To Apologize

National Archives

Even after the truth came out, the Public Health Service didn’t apologize. John R. Heller Jr., the head of the Division of Venereal Diseases, publicly responded with a complaint that the Tuskegee experiment was shut down too soon. “The longer the study”, he said, “the better the ultimate information we would derive.”

Eunice Rivers insisted that none of her patients nor their families resented her for her part in the study. “They love Mrs. Rivers,” she said. “In all of this that has gone on, I have never heard anyone say anything that was bad about it”.

The Tuskegee Institute apparently agreed. In 1975, three years after the Tuskegee experiment became public knowledge, the institute presented Rivers with an Alumni Merit Award. “Your varied and outstanding contributions to the nursing profession,” they declared, “have reflected tremendous credit upon Tuskegee Institute.”

The families of the patients, however, didn’t echo the support of Rivers. “It was one of the worst atrocities ever reaped on people by the Government”, said Albert Julkes Jr., whose father died thanks to the study. “You don’t treat dogs that way.”

The Aftermath

Wikimedia Commons

After news of the study came out, the American government introduced new laws to prevent another tragedy such as this. These new laws required informed consent signatures, accurate communication of diagnosis, and detailed reporting of test results in every clinical study.

An Ethics Advisory Board formed in the late 1970s to review ethical issues concerning biomedical research. Efforts to encourage the highest ethical standards in scientific research are ongoing to this day.

In 1997, the U.S. government formally apologized to the victims. President Bill Clinton invited the last eight survivors and their families to the White House and apologized to them directly. He told the five survivors that attended, “I am sorry that your federal government orchestrated a study so clearly racist. … Your presence here shows us that you have chosen a better path than your government did so long ago.”

- https://allthatsinteresting.com/tuskegee-experiment-syphilis-study

- https://www.grunge.com/220418/the-crazy-true-story-of-the-tuskegee-syphilis-experiment/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tuskegee_Syphilis_Study

- https://exhibits.stanford.edu/saytheirnames/feature/tuskegee-syphilis-experiment

- https://www.history.com/news/the-infamous-40-year-tuskegee-study

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4568718/

- https://www.easternct.edu/news/_stories-and-releases/2020/11-november/from-tuskegee-to-covid-19-why-african-americans-do-not-participate-in-research.html

- How Greed Made Piracy Great Again - February 1, 2026

- Why PC Gaming Is No Longer Affordable - February 1, 2026

- Why Student Loans Are a Scam - January 18, 2026